When you’ve been quail hunting as long as I’ve, you notice a few things about upland hunters. First, they love their dogs. Second, they love their shotgun almost as much as their dog. Third, they’re stubborn as all get out—a quality they share with their aforementioned dogs.

Sometimes this simply manifests as a life-long hunter who will endure far too much hardship (cactus, snakes, heat, cold, countless miles, rolled ankles—you get the idea) to get a glimpse at a bird the size of a softball. Then, you have Dr. Ron Kendall, who takes this stubborn, “never say die” attitude to a level that’s creating real change for wild quail and their populations.

Known to some as “The Quail Doctor,” Ron and his team at Texas Tech University have been spending decades of their time trying to bring wild quail back to their healthy state on the landscape. I had the privilege to talk to Dr. Kendall about the sad story of the bobwhite quail, the glimmer of hope in its future, and why our hunting culture is essential to its survival. The good news? It seems like he and his team are winning.

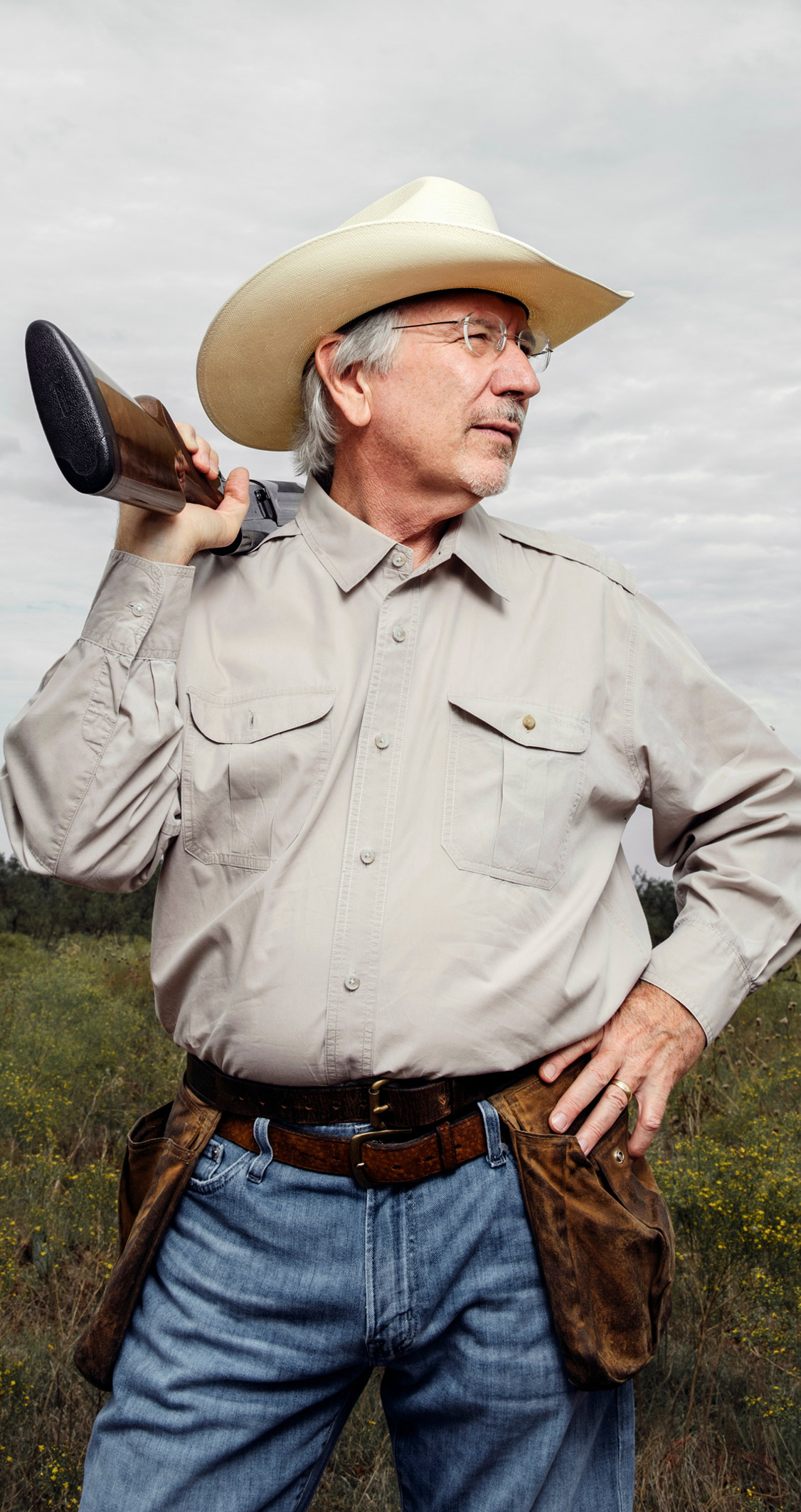

Here’s Dr. Ron Kendall, aka “The Quail Doctor.”

Photo courtesy of Texas Tech University.

Levi: Let’s start at the beginning. What kicked off your love for wild quail?

Dr. Ron Kendall: I grew up in a fairly rural area in the low country of South Carolina. It was a fabled quail-hunting area. My grandfather lived nearby and mentored me beginning at just six years old, where I’d walk behind him while he hunted. He had a Llewellin Setter named Fannie who was phenomenal—she could trail a covey for 200 or 300 yards. It was amazing.

The quail season always opened on Thanksgiving Day, so my mother would adjust dinner so I could go quail hunting. I remember the first time my grandfather and I went hunting on my twelfth Thanksgiving and, this is the truth, we started right out of my front door with Fannie. I got three quail that day with three shots using a .410 single-shot shotgun. I was so elated. After the first covey rise, Grandaddy actually let me take Fannie and go by myself for the next week or two. I can’t believe he let a 12-year-old do that. I was a pretty mature kid, but I loved Fannie and she actually taught me how to quail hunt. She lived for years after that.

LG: Sounds like the quail hunting wasn’t too shabby over there.

RK: It was fantastic. Within a five-mile radius, I walked it every chance I got and there would be between 60 and 80 coveys of quail. I had ‘em all marked down on a map. I was really into it. The sad part of the story is that I’m not sure there’s one covey there now. They’re gone. In South Carolina, quail hunting was an incredibly important thing from a cultural standpoint, and now it’s essentially gone unless you’re spending major money for tracts of public land.

I still meet up with my childhood friends in South Carolina. We’ve been hunting partners for 60 years, and over the past fall season, it was hard to find a single wild quail, much less a covey. I've seen this change in my own lifetime and it really shocks me that something I could love so dearly could be gone so quickly. I used to sit on the couch watching a college football game and a big covey would walk across my backyard.

"Within a five-mile radius, I walked it every chance I got and there would be between 60 and 80 coveys of quail. I had ‘em all marked down on a map. I was really into it. The sad part of the story is that I’m not sure there’s one covey there now."

LG: I’m curious what makes a kid want to dedicate his life to quail. Most folks stop at hunting.

RK: I was very interested while quail hunting all through school and high school, but when I went to the University of South Carolina, I knew I wanted to do something in environmental science. I majored in biology and minored in chemistry, and did very well in both. My professor wanted me to go to medical school and he said his endorsement would get me into just about any medical school. It was a big decision, but I told him I wanted to be an environmental scientist. He thought I was crazy [laughs]. This was around 1973.

I graduated from the University of South Carolina and got my master’s degree at Clemson University in the wildlife department. My focus was on wildlife toxicology, although, we hadn’t even coined the name yet. I published four papers at Clemson and was then recruited to Virginia Tech. Clemson offered me an opportunity to stay there for my PhD, but at that time, Virginia Tech had one of the top programs. They were writing the books, so I went up there for my doctorate, where I studied lead and lead shot exposure in mourning doves.

Long story short, I was identified by the Environmental Protection Agency and they selected me for a fully paid traineeship to go to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for special training with their toxicology department. I graduated from Virginia Tech one day and left the next. I was essentially creating my own career, which eventually led me to Western Washington University, Washington State, back to Clemson, and then eventually out to Texas Tech.

LG: When you eventually made it out to Texas Tech in the late ‘90s, did you see an east-to-west trend of declining populations?

RK: I think so. Historically, we’ve had wild bobwhite quail in about 25 states. Now, it’s estimated that as much as 90% of the quail population has disappeared, to the point where sustainable hunting just isn't available in most places. This is due to several factors, including human development and habitat loss, as well as parasitic factors like the cecal worm, which has been a focus of our research at the toxicology lab.

The Rolling Plains region of West Texas is one of those last strongholds, as well as South Texas, of course, whereas the quail are essentially gone in East Texas. But we’re not without problems in West Texas, and we tend to see dramatic population shifts. If you go back the last 50 years and look at data from Texas Parks and Wildlife, every time we get a peak, we get a crash. Peak, crash, peak, crash. We saw a crash in 2010 on one of the best quail-managed properties in West Texas, and it took five years for that population to recover.

Through our work at the university, we identified these parasitic infections in quail and discovered how widespread and intense they could be. We set up multiple demonstration ranches as a way to gauge the problem and test solutions, which is how we developed Quail Guard, a medicated feed to treat parasitic infections in quail. On our test ranches that we’ve been treating with Quail Guard for the last few years, we’re not seeing these crashes. They are sustaining hunting. There’s still a lot of discourse surrounding the cause of population decline, whether it’s habitat or environmental shifts or parasites or whatever. That being said, we’ve got 50 scientific publications on this topic—and the real test for me is whether or not the landowners are seeing quail.

“Historically, we’ve had wild bobwhite quail in about 25 states. Now, it’s estimated that as much as 90% of the quail population has disappeared, to the point where sustainable hunting just isn’t available in most places.”

Photo by Joe Crafton of Park Cities Quail Coalition.

LG: The proof is in the birds.

RK: That’s the way I see it. I’m just trying to come up with a solution because it’s dear to my heart. I love to eat quail, but I don’t shoot that many of them anymore. I just really enjoy the birds, and you don’t get to this place unless you love it. We have approached this problem from a very scientific perspective and, in the world of scientific literature, you don't get an FDA registration for medicated feed wildlife unless you’re willing to spend about a decade of your life doing it.

LG: I read a quote where you described Texas as “The Alamo” for wild quail populations. What is it about West and South Texas that has protected them more than some other areas? Is it lack of pressure on private land or is there something about the landscape?

RK: It’s a relatively stable landscape. As you know, West Texas is mostly ranch land, and it has hardly changed in the last quarter century. I think that may have been part of sustaining the populations—and I’d say the same is true in South Texas. Of course, habitat is very important, but there’s more at work with these populations than just habitat.

I stand by my statement that I view West Texas as "The Alamo" of wild quail hunting in North America. There are not many places you can go and find 20 to 30 coveys in a day, but we're seeing that on our treated ranches. That’s the signal that we’re hitting that target. Conservation organizations have played a pivotal role, too. I applaud Park Cities Quail Coalition and the Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation for raising money to support quail conservation. They’ve been big players. It’s important to note that this has been addressed by sportsmen and not by federal agencies or even state agencies.

“I stand by my statement that I view West Texas as 'The Alamo' of wild quail hunting in North America. There are not many places you can go and find 20 to 30 coveys in a day.”

LG: A lot of non-hunters don’t understand that being a hunter and a conservationist aren’t mutually exclusive. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. What can hunters do to continue supporting wild quail populations?

RK: That’s a great point. The sporting organizations stepped up to fund all of this. Without quail hunters, we’re not going to have quail conservation. If we’re talking about what people can do to help, I would encourage hunters to stay with it. Their hunting dollars create revenue for quail management. Then, if you’re a landowner, you’ll have to make a decision if you’re going to treat them for parasites or not. To me, it’s a no-brainer. Everyone treats their dog for worms, why wouldn't you treat birds? It seems to be a great option for sustainability.

Thirdly, contributing to these sportsman’s organizations is very important because they are making a difference. The reason we have Quail Guard today is because of Texas’s sporting culture and hunters stepping up and saying, “We've had enough.”

“Without quail hunters, we’re not going to have quail conservation.”

LG: That’s a good segue into my last question. As a transplant hunter, what sort of connection do you have with Texas hunting culture now?

RK: When I first started hunting out here, I was shocked at how open it was and how many quail there were. I remember we went to this ranch when we got to Texas in the fall of 1997, and my son would go with me. He was only about three and a half years old, but he had a red Mattel Jeep that he drove around behind me that went about five miles an hour. He could keep up with me and I’d throw quail into the Jeep. He loved that Jeep.

In the east, you’re hunting smaller tracks of land. It’s just tighter. So, overall it took me a while to get used to the big country. But, just like my grandpa’s dog Fannie, it helped to have some very fine bird dogs as teachers. My favorite was my English Setter named Skagit. He was named after the Skagit River in Washington. I successfully hunted nine species of game birds with him.

We were hunting this property one day, and I saw him headed toward this prickly pair patch. Skagit had hunted all across the United States and even into Canada. He would break through any brush—he was fearless. Unfortunately, he’d never seen prickly pear. I tried hollering at him but, man, when he hit that prickly pear it took me a long time to get those spines out of him. That was a big difference from the east coast [laughs]. After that, he looked like a ballerina going through those prickly pear patches. I’ll never forget that day.

"Skagit had hunted all across the United States and even into Canada. He would break through any brush—he was fearless. Unfortunately, he’d never seen prickly pear."

LG: It’s funny which days decide to stick with us.

RK: Isn’t it? Skagit lived to be 17 years old. I have a picture at my home office that I took of him hunting. It’s his last point. He was 16 years old and I had an important guest with me—he shot two quail on this property and Skagit retrieved them both. I only hunted him for about 30 minutes at the end of the day. I still remember that guy watching Skagit chasing those birds at 16 years old. He couldn’t believe it. That dog had so much heart. He turned 17 that January and died in March from kidney failure. I’ve had some amazing dogs, but he was my favorite. Time flies. Looking back, quail hunting has been a major part of my life, but I guess I’m more of a quail conservationist now than I am a quail hunter. It’s funny because for so many years I used to have to organize everything. I'd get the bird dogs ready to go, and then my son Ronnie would always go along. Now, things have flipped. He coordinates everything.

LG: He’s come a long way from the red Jeep, huh?

RK: [Laughs] I guess so. I get so busy sometimes, but we love to quail hunt together. These days, he’s as good of a shot as me, if not better, which I’m fine with. I just love to see those birds fly.

Header photograph by Trevor Paulhus.

Unless otherwise noted, all other photography by Steve Schwartz.