My dad was the kind of person who helped a family stick together. After he passed away in 2016, I had a realization that the Goode men had lost their “glue.”

Three generations had drifted apart over the decades, and it was high time to ring the proverbial dinner bell and bring everybody home—for us, this has always been the Texas coast. It took a ringleader and some planning to get us all together, but damn, was it worth it.

Before you think this is just a chance for me to wax poetic about family, well, that’s only partially true. I figure my experience could hold true for a lot of us—Texans live in a big state, and it can be easy to drift away from those who matter most. Namely, those folks who share your last name. Maybe it’s time to close the gap and rekindle those connections, however that looks for you.

In lieu of preaching, I’ll just tell you why it mattered to me.

“Three generations had drifted apart over the decades, and it was high time to ring the proverbial dinner bell and bring everybody home—for us, this has always been the Texas coast.”

Closely tied, distantly tethered

There’s a reason I chose the coast for our family gathering—saltwater runs in our veins. The coast is where both sides of my family put down roots generations ago. My mother’s side came from Italy via New Orleans, where her father took up the clarinet and made a living as a professional jazz player in the French Quarter, eventually moving to Texas to work for Dow Chemical. On my dad’s side, his father also worked at Dow Chemical and they lived in Clute, Texas, where my dad could throw a rock and hit the Gulf of Mexico.

As a single-income family with five kids, my dad grew up enjoying the bounty of the coast because he had to—those oysters, trout, and redfish helped feed the family when times were tight. Eventually, that deep connection to the water was passed down to me and my family.

“As a single-income family with five kids, my dad grew up enjoying the bounty of the coast because he had to—those oysters, trout, and redfish helped feed the family when times were tight.”

My dad had two brothers—Uncle Joe and Uncle John, who are now 80 and 85 years old, respectively. Uncle Joe and I have stayed close. We’re both fans of live music, and at eight decades old, he can still keep up with me—glass of Jack in hand—at just about any music festival we nab tickets for. As for Uncle John, he’s the classic older brother—responsible, conservative, and reliable. As a petroleum engineer, he founded one of the largest pipeline companies in Venezuela, but was forced out of the country when the government crumbled and Hugo Chávez swooped in, nationalizing most of the industry. He and his wife (a Venezuelan native) now live in Houston.

With both of them back in the States, I felt like the timing was perfect to get the boys back together.

For the record

Our getaway was a rare opportunity to mobilize all the Goode men I know—three generations of us—over to the coast for some fine eats, a friendly fishing tournament, and some storytelling of the highest caliber.

We borrowed a buddy’s beautiful Galveston home on the water. We booked a mariachi band. Best of all, we found a way to put our family’s narrative on the record. I was able to call in a colleague from Texas Foodways (a subset of the Southern Foodways Alliance, an incredible organization that documents and preserves food culture in the South) to interview my uncles about their time on the coast. None of us are getting any younger, and we figured there’s no time like the present to set our stories in stone.

As soon as Uncle Joe and John stepped foot in town, the memories flooded back. Our stay was only about 20 miles from their childhood home, and it’s amazing how a place can unlock those stories that have been tucked away in our subconscious. (It also helps that the Texas coast doesn’t change much—it largely looks the same, despite more than a few hurricanes that have rolled through since their early days.)

We toured their childhood home after the current homeowners were kind enough to let us in. We even went by Harden’s Dairy Bar, an iconic burger joint in Lake Jackson where Uncle John used to flip burgers back in 1962. The cook invited him to pick up where he left off, and we watched my uncle flip burgers the same way he had decades ago. He made the local newspaper.

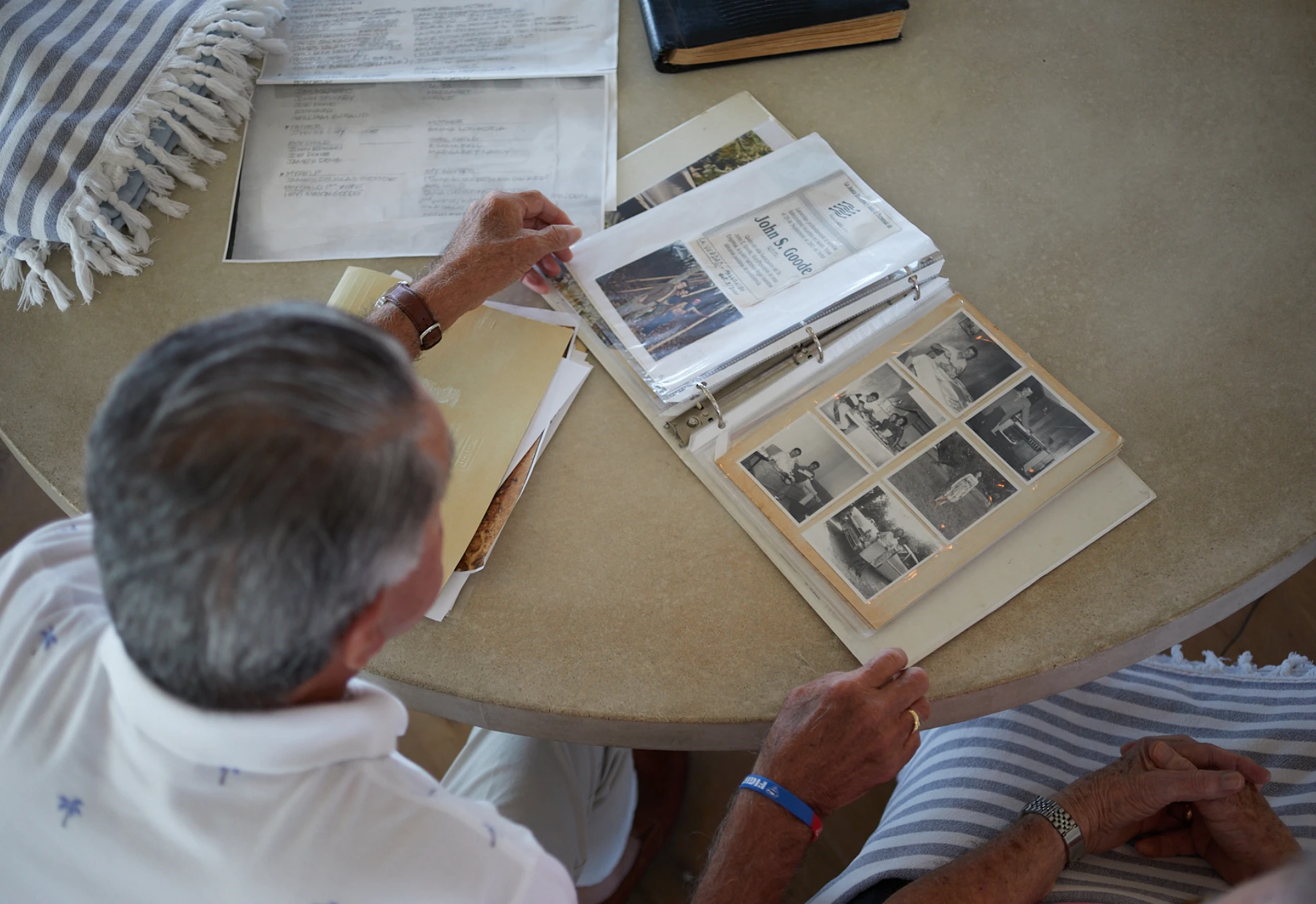

John Goode (left) and his younger brother Joe (right) pore over old family photos.

“I can vividly picture my uncles cruising through Old Mexico with a mariachi band as their only soundtrack, save for a stiff breeze coming through the windows. These are the stories I don’t want to lose.”

John Goode (left) and his younger brother Joe (right) pore over old family photos.

Inspired by these memories, Uncle John told us a story I hadn’t heard before. After graduating from A&M, a local car dealership would finance a car for you if you showed them a job-offer letter—which he had from Exxon. John got his car, got Joe, and the two promptly took off on a road trip to Mexico, visiting family and seeing the sights. He recalled stopping to pick up a group of hitchhikers—a mariachi band trying to get to their next gig—under the agreement that they’d play for them during the drive.

Even though this story unfolded well before my days, I can vividly picture my uncles cruising through Old Mexico with a mariachi band as their only soundtrack, save for a stiff breeze coming through the windows. These are the stories I don’t want to lose.

What’s your big excuse?

This article isn’t about our weekend. It’s about what the weekend meant. I don’t need to tell you about the oysters we cooked up, or the cocktails, or the mariachi band, or the fishing tournament. I don’t even remember who won.

The weekend was about family. During those days on the coast, our name didn’t represent barbeque. It didn’t represent seafood. It didn’t even represent Houston. It represented John, Joe, and Jim. It represented a bond that can’t be broken, no matter the difference in our personalities or the distance between us.

Here’s the thing. You have a last name—dig into it. Do a little “blood test.” Dig up all of the skeletons from your family’s past, and you just might uncover a few Mexican road-trip stories along with ’em.

“During those days on the coast, our name didn’t represent barbeque. It didn’t represent seafood. It didn’t even represent Houston.”

I can’t bring my dad back. Uncle John and Joe will be gone someday, too. So will I. When that happens, the only thing that remains are the stories we tell each other. I’m proud to say my kids will have access to these stories whenever they want them, whether that’s tomorrow or 30 years from now.

If you’ve been meaning to get the band back together, there’s no time like the present. Give your uncle or granddad or cousin a call. You never really know what’s going to happen, but that makes for the best stories anyway. That, and a good mariachi band.

Photography by Jody Horton.